Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Detecting Launching

The question for this section is,

Can humans perceive causal interactions?

Let my try and show you stimuli that were used in an experiment (without yet telling you

anything about the experiment). What do you see?

[If the animation doesn't work, there's a static version on the next slide.]

Thines et al (1991)

OK, so adults: (a) verbal reports. So what?

‘There are some cases … in which a causal impression arises, clear, genuine, and unmistakable,

and the idea of cause can be derived from it by simple abstraction in just the same way as the

idea of shape or movement can be derived from the perception of shape or movement’

\citep[p.\ 270--1]{Michotte:1946nz}

Adults will also report experiencing causal interactions including pullling, ...

Scholl & Tremoulet 2001, figure 2

... disintegration ...

... and bursting.

detecting launching effects at 6 months

This effect, or one very like

it, can also be found in infancy.

Of course, six-month-olds can't tell us about their expeirences.

So how can we tell that they detect launching effects?

Infants at around six months of age seem also to distinguish launching from other sequences,

much as adults do \citep{Leslie:1987nr}.

[nb: Several people have discussed this in seminars so I won't discuss it here (the reference is on your handout).]

In their experiment, they compared two groups of infants.

The first group was habituated to the top display, which is just the sort of animation Michotte

used to get reports of causal experiences in adults.

After habituation, this first group was then shown the same display except that the direction was

reversed.

Meanwhile a second group was habituated to a display like the top display here except

that there was a delay between the first object stopping and the second object starting.

This delay would mean that, in adults, there are no reports of experiences of a causal interaction.

After habituation, this second group was shown the same display except that the direction of

movement was reversed.

Of interest was whether the first group showed greater dishabituation to the reversal than

the second group.

How could this tell us anything about infants' experiences?

Suppose that infants do not have anything like what adults report as an experience of causation.

They they experience merely patterns of movement.

And, in this case, reversing on sequence should create no more interest than reversing the other.

But now suppose that infants do have something like what adults report as an experience

of causation?

Then, when reversing the first sequence, there are two changes: there is a change both to the

movement and to the character of the causal interaction. To put it informally,

reversing direction means that the patient of the interaction becomes its agent.

So the hypothesis that infants' experiences of Michotte-like stimuli resemble adults

predicts that there will be greater dishabituation when the first, `direct launching` sequence

is reversed.

Leslie & Keeble 1987, figure 4

And this is just what the researchers found.

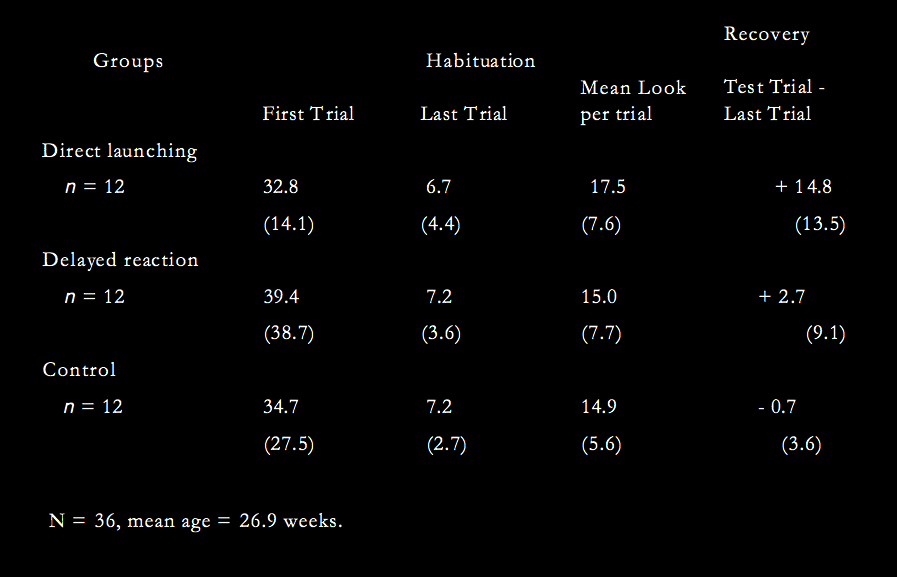

The table shows mean looking times in second (with standard deviations in brackets).

The control group was just like the direct lanunching group except that there was no reversal

Leslie & Keeble 1987, table 4

Heider & Simmel 1946, figure 1

Can humans perceive causal interactions?

So can humans, adult and infant, perceive causal interactions?

So far I don't think we have strong reasons to accept that they do.

In infants we have discrimination and in adults we have verbal reports.

But we shouldn't trust verbal reports.

After all, people will say all kinds of things about their experiences.

This is nicely illustrated by a famous experiment on apparent behaviour by \citet{Heider:1944ts}.